Respondez S’il Vous Plaît

When an illustration project is allowed to be a dialogue, a call-and-response with another.

The images in this post are all from the final piece - read on to see the video of them put together with a voiceover.

Earlier in the summer I was approached by a Doctor / professor of medicine at Duke University, who has become a frequent collaborator of mine in projects about shame and medicine. He was getting in touch to let me know there was a bit of grant money available for me to work on making something in response to a poem that had been written by a medical student. That was basically the extent of the brief: “We have some money, we have a poem, can you make something out of that, by August?”

I feel really lucky to be in a position where I can take on pieces of work like this, where someone who trusts me based on working with me before, can take a risk and think “Hannah will make something good”, and believe in me enough to not direct the process any more than that. Having someone believe in me and give my creative process the space that it needs, is pretty transformative for me as a person who has often struggled with very harsh perceptions of their own self-worth.

So, I arranged to take a first look at the poem.

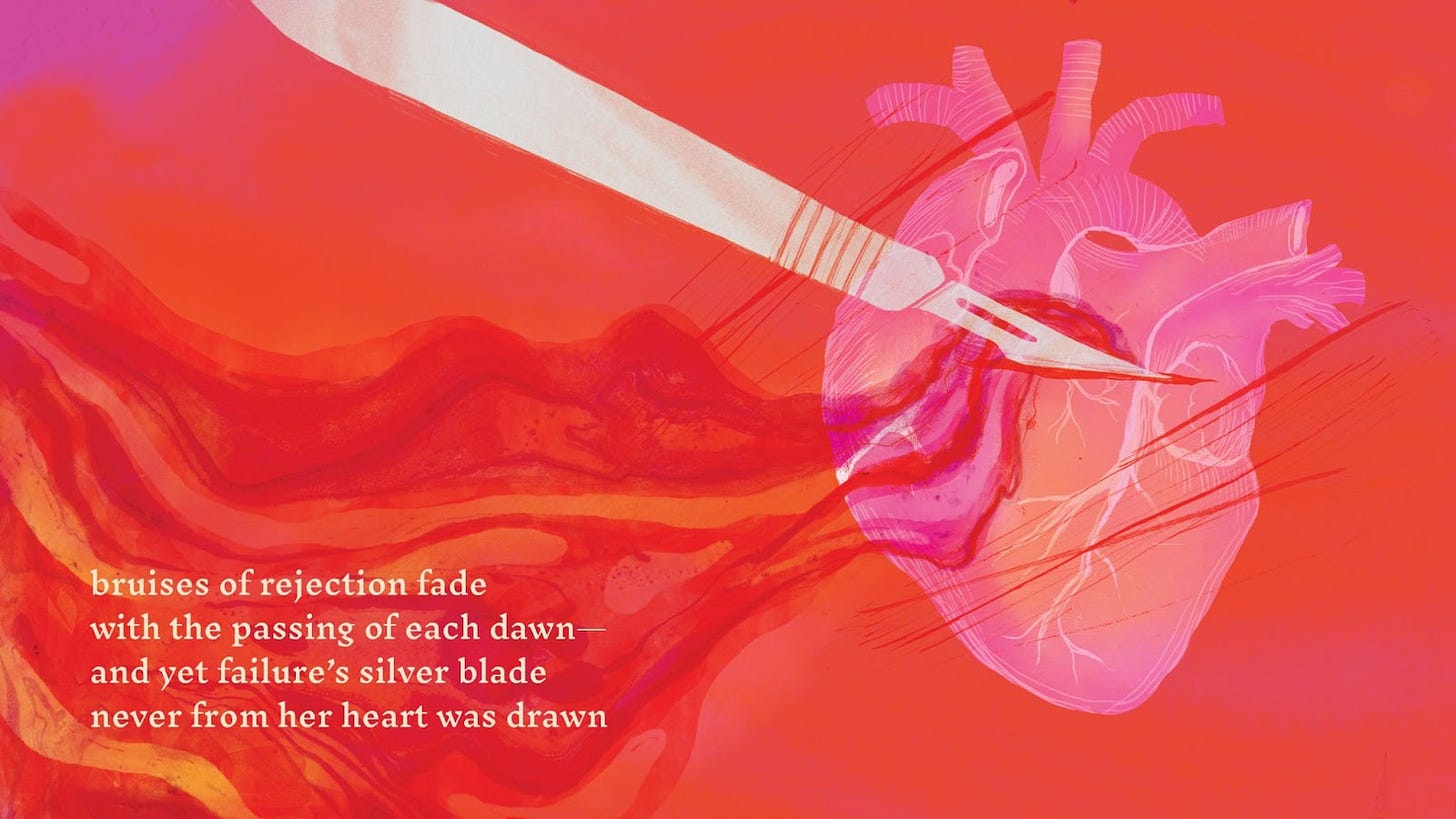

An extract from the medical student’s poem. You can read the full text here

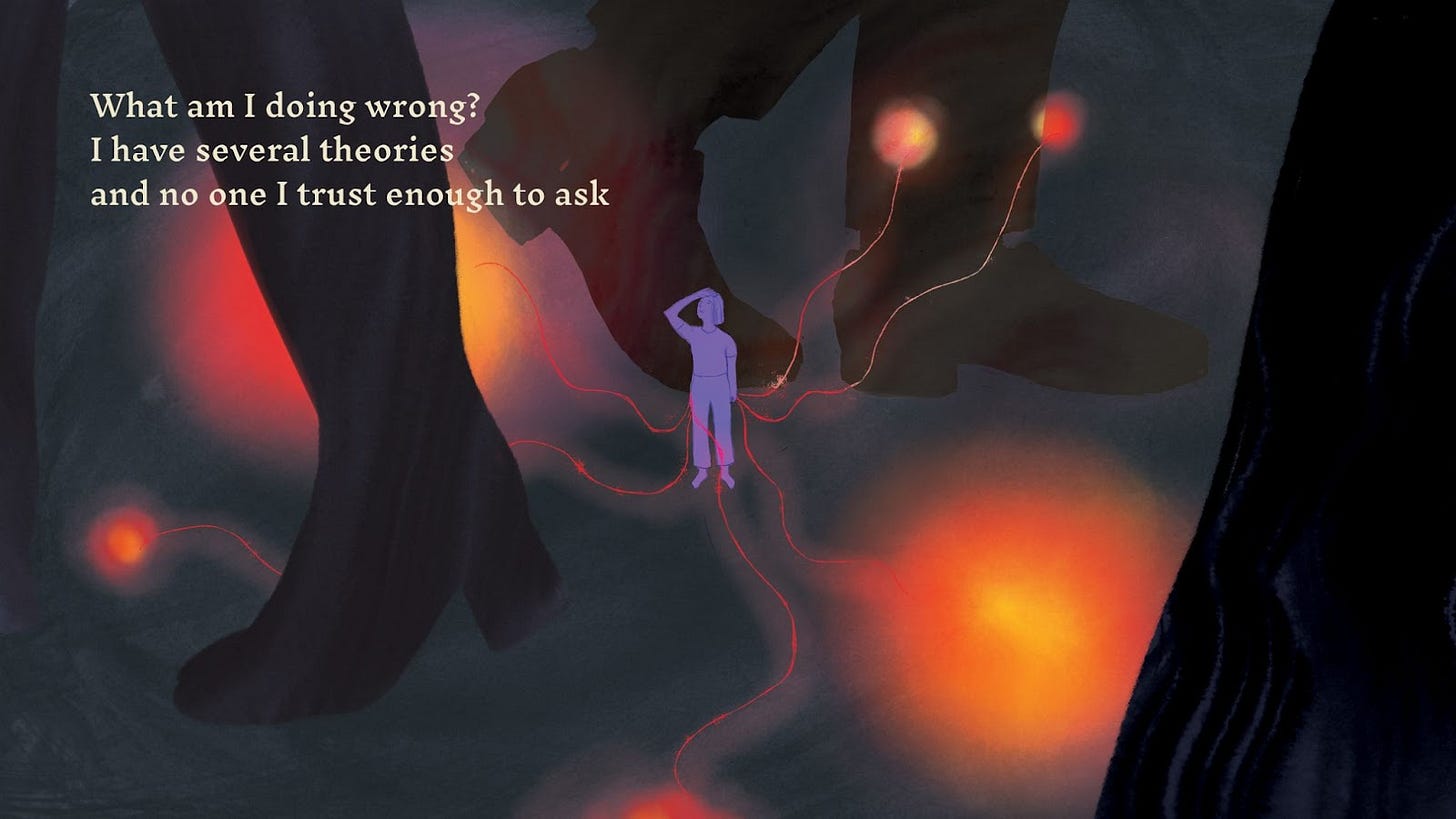

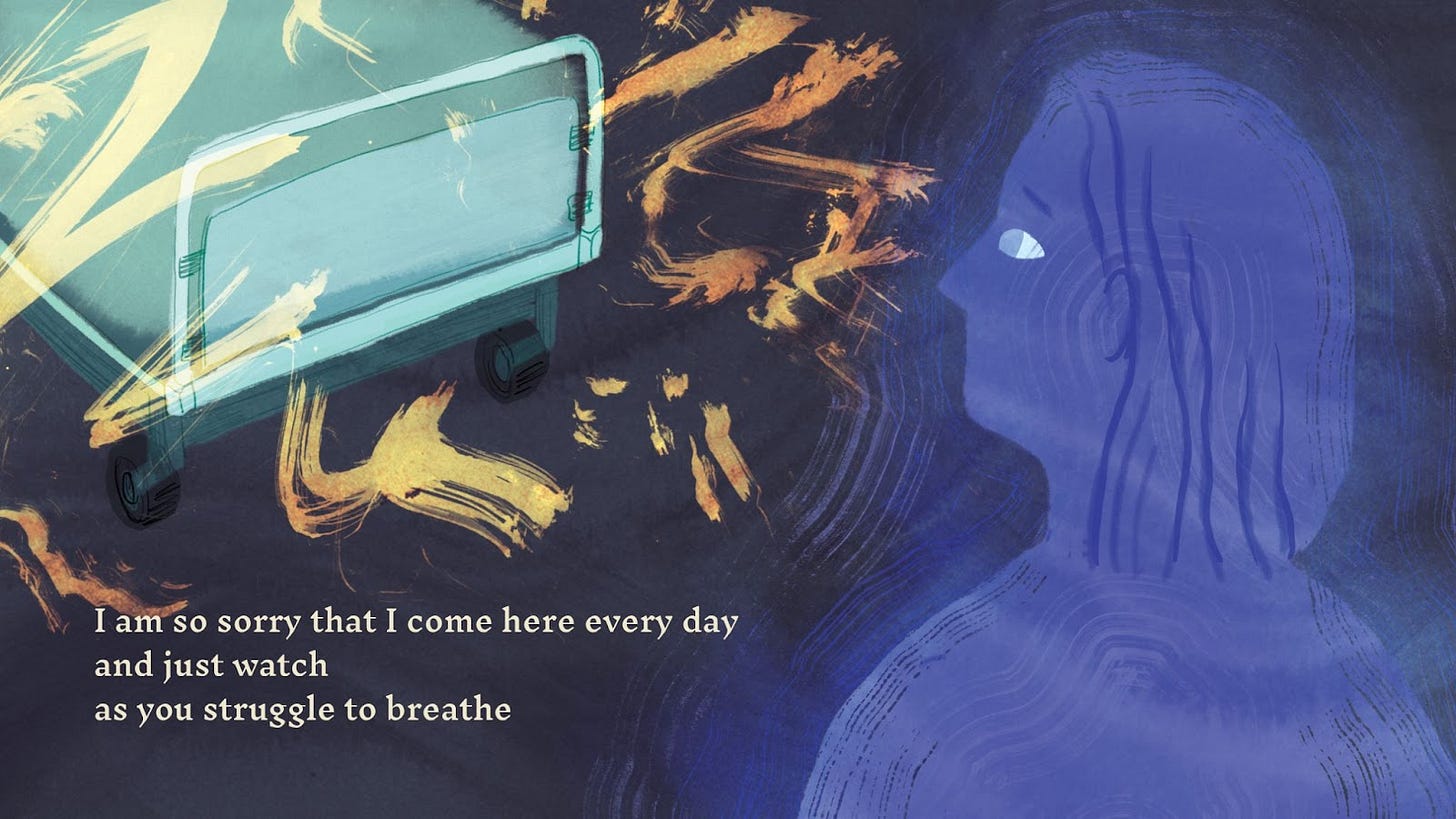

The poem was an intensely personal account of the student’s suffering, self doubt, shame and despair, and they hadn’t originally written it knowing that it would be something they would share publicly. The force of their feeling was palpable - bodily and fleshy in its intensity - and I hadn’t expected to be given something to work with that cut me with such a sharp edge.

It immediately felt important to start a dialogue with the student, to understand something of what they had put into their writing, to hear some more about their experience, and to acknowledge the vulnerability inherent in them offering this piece of writing for a collaboration with someone who was a total stranger.

What we agreed was that I would create images based on my own responses to the poem, and that I would share these as I went along, but we wouldn’t do a process of reviewing and amending the images: in other words, I could create what I liked. The images I made would be assembled into a video with a voiceover reading the poem, for which we would hire a voice actor, as the student wanted to remain anonymous. I explained to the Doctor who had contacted me, that this is what we had agreed, and that this would allow me to create many more images with the time I had available, than if I had needed to go through an approvals and amendments process. The fact that they agreed to this showed that they understood that the images would be part of a dialogue between the student’s words and my creative process, and I think they found this to be a sensitive approach to the material. I wish all commissions could be like this! But I have found that there is often much more room for trust in this work than there might seem.

Over the past year, my partner and I have been involved in a very difficult process of dealing with planning permission for a house we want to build together. It’s something that has been massively challenging, and means so much to us both. We’ve had to learn to trust the people we are working with, but also know when to push back; we’ve had to draw on strength that I didn’t even know was there. One thing that has been an eye-opener in this process, is that we have discovered that even when you follow what you believe to be hard and fixed rules about a collaboration (i.e. a council’s planning policy), when you establish a dialogue with the person on the other end, it’s possible to find doorways that you didn’t know were there. When you’re involved in a process like this, you’re dealing with a person’s individual, personal interpretation of a set of rules, rather than those rules existing as some kind of objective fact. This means that it is a process about dialogue, about uncovering and understanding what the other person is saying; hearing what their priorities are - feeling for where they will budge and where they won’t; responding to that while also not backing down on your own needs.

I am starting to learn that a lot of work is actually about relationships. Maybe that’s obvious to many of you, but it’s something that’s dawning on me as I understand more about my own sense of agency, and get more in touch with my assertiveness and my aggression. I’m discovering that I do far, far better work, when I put my foot down about something that I believe is necessary, and that very often I hate the results of commissions where I’ve conceded too much.

After finishing the illustrations and assembling them into a film with the voiceover (with help from my friend Tommy Parker who is a general wizard at everything) I had another conversation with the medical student to talk about what it was like to collaborate, and what they thought of the end result. They said they had never considered that their writing had within it the potential for the creation of something much bigger, and working on this process had made them think about whether their writing practice should form a more prominent part of their medical career in some way. We talked about writers who have been doctors (like Mikhail Bulgakov, who first wrote A Country Doctor’s Notebook before he wrote The Master and Margarita), and I shared that the medical students I’d worked with earlier in the year had built a journalling practice into their life as clinicians in a way that offered them a channel for feelings like anger, frustration, doubt and grief - feelings that aren’t always welcomed when you’re being trained to be an invulnerable doctor who doesn’t make mistakes, and who has to be embodiment of health and strength.

I’m really happy with the way this piece turned out. You can watch the final film below (warning: there are themes of suicide).