This autumn I’ve been working with researchers to develop illustrations and icons for trauma-informed training that will be used with a local police force. The training focuses on bringing awareness to the relationship between trauma and shame, and how these states can cause people to behave and relate to themselves and others. This isn’t the first time I’ve made work about shame: last year I worked with the Shame and Medicine project to create illustrations about shame in medical education, based on real interviews with American medical students.

In my image-making practice I work a lot with subject matter relating to feelings, emotional states, mental health. When I’m working to a tight deadline, and particularly if I don’t have someone’s personal story to draw from, it’s hard to find new ways of visually representing complex states of being. Often when I have to make an image very quickly, I resort to a combination of over-used clichés around posture, and moody colours and textures. I do think this sort of image works to a certain extent, as it’s quite simple, and the good thing about clichés is that they have a directness in their legibility. This can be particularly useful in situations where you’re trying to communicate something quite complicated to an audience who don’t have much time to find a way in. However, as a colleague reminded me this week, clichés function by perpetuating stereotypes. So how do we communicate something very sensitive and complex, in a way that gets the message across quickly?

An illustration I made about regret, for a poetry collection about desire.

In an ideal world, when I’m making any image, I want to have a story to work from: whether that’s my own, someone else’s lived experience, or a long-form piece of text that explores the subject matter with a degree of nuance; all the better if it’s written or spoken in someone’s own words and is not over-edited. In this situation, you can fish out the words from the story that give you the beginnings of an image - and not necessarily from the point of view that would be the most obvious. This is a great way to open up the subject, because you’re using the fabric of the person’s experience, but a lesser-seen corner of it - this allows you to access something more subtle.

An illustration I made for Mens Mental Health organisation Alright Mate about overwhelm

However, very often as an illustrator you’re working with only a general concept, perhaps something quite unspecific. It might be as broad as: ‘make an image of this emotion’. In this case, where do you begin? I tend to sit there, looking blandly at an unfixed point to the right of my computer monitor, thinking “what does it feel like to be feeling that feeling?”; “how do I feel in my body when I experience that?” or “what do people look like when they’re feeling this way?”. This approach can get me only so far, as I’m conjuring something out of nothing. Inevitably, this means I’m drawing on vague associations and shallow impressions that are left over in my mind, formed from brief encounters and the residue of popular culture.

An illustration I made about feeling anxious and preoccupied by the news cycle and checking my phone during the first Covid-19 Lockdown

The issue is: how do we go about representing something that’s happening inside us? With images that explore emotion, why is there a tendency to think that the first point of call would be to attempt to show what emotion looks like from the outside? How do you make an image that communicates an inner sensation; a feeling like dread, anxiety, horror, disgust; or feelings that are uncommunicable? Trauma is something that, by its nature, we most likely can’t find words for: when something unspeakable has happened to us, something unfathomable, that threatens the stability of our existence and calls everything into question, how can this be conceptualised at all?

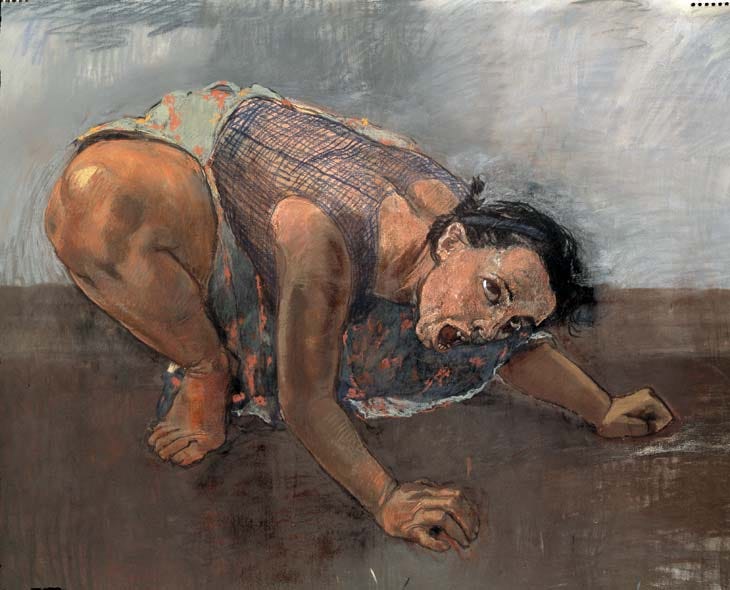

It may be that this is the limit of image-making, for a topic like mental health: illustration presented in traditional formats is not experiential enough. I’m not convinced this is true: some of my favourite visual art, even in the 2D plane, I like because it provokes a visceral reaction. Take Paula Rego’s work: when I look at it, I feel it in my body.

Paula Rego - Dog Woman

Is it that to really evoke a feeling in a 2D image, you need to have some direct, visceral and embodied reference, beyond words, that you draw on?

When I worked with the Shame and Medicine Project, I needed to find a way of illustrating a ‘shame journey’ - an image of an embodied experience of shame, to represent the type of shame experiences that can happen to medical students during their training. I worked very closely with Dr Will Bynum IV, M.D. who shared his research for The Shame Conversation, and gave me access to interview transcripts and coded data taken directly from American medical students talking about their real life experience of shame, in their own words. This allowed me to read some interesting and unusual ways of articulating shame, and in the words of the Medical Students I came across the following physical sensations:

Feeling hot

Being too big (but also the tension of wanting to take up space and be on top form or the best)

Being seen - being self conscious (but also the tension in wanting to be seen and appreciated)

Weight in gut

Tight chest

Emotions falling out of your eyeballs

And then there were emotional and psychological motifs, like:

Battling voices (sense of internal 'we')

Irrational vs rational

Desire for closeness with superiors - wanting to be special

Imbalance or instability - the threat of things crumbling down and losing control

It was here, in the text of lived experience, that I drew the inspiration for the images I wanted to make about shame. You can view the final pieces below: a sequence that shows how a shame experience can unravel:

In this image, a student feels hot and self-conscious, they have to flee the scene and hide in a toilet cubicle (something I’ve done many times!)

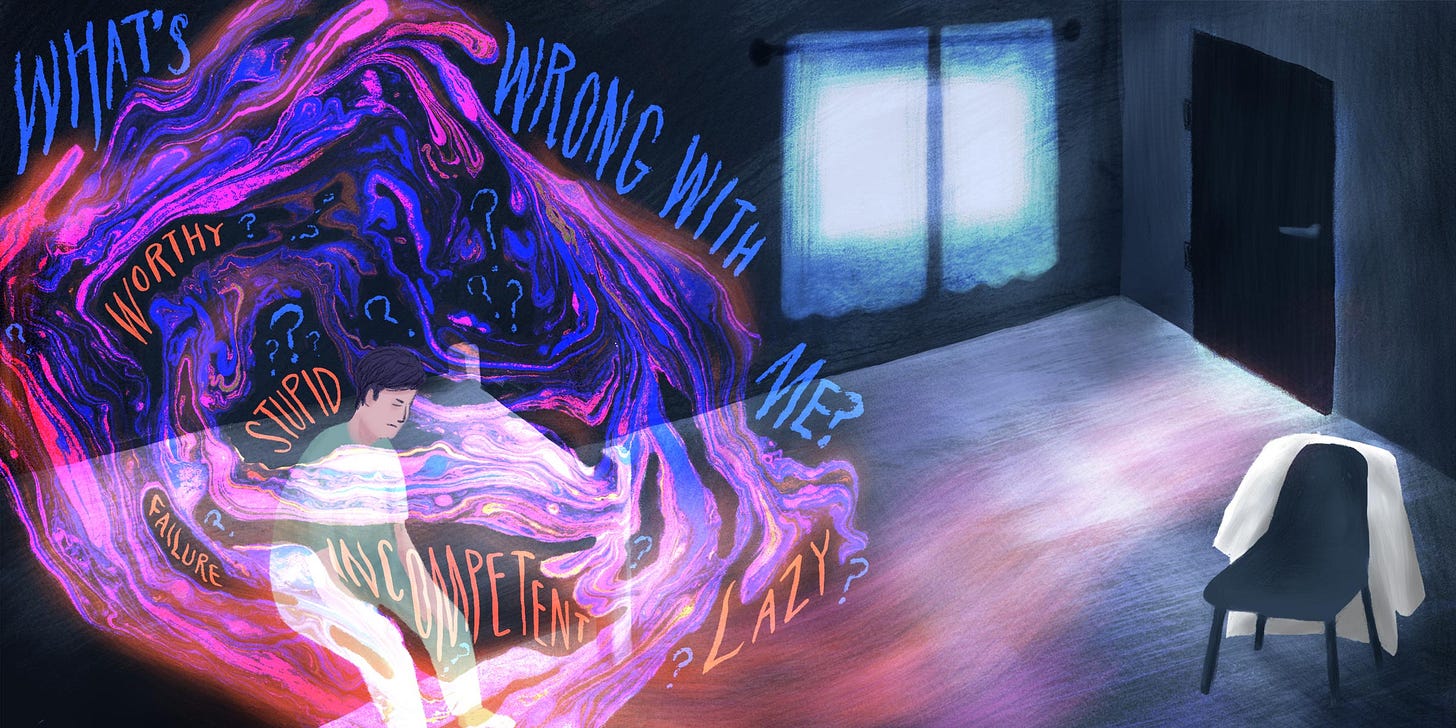

Next we see them shut in an on-call room, with words circulating, paranoid, persistent feelings of being ‘bad’

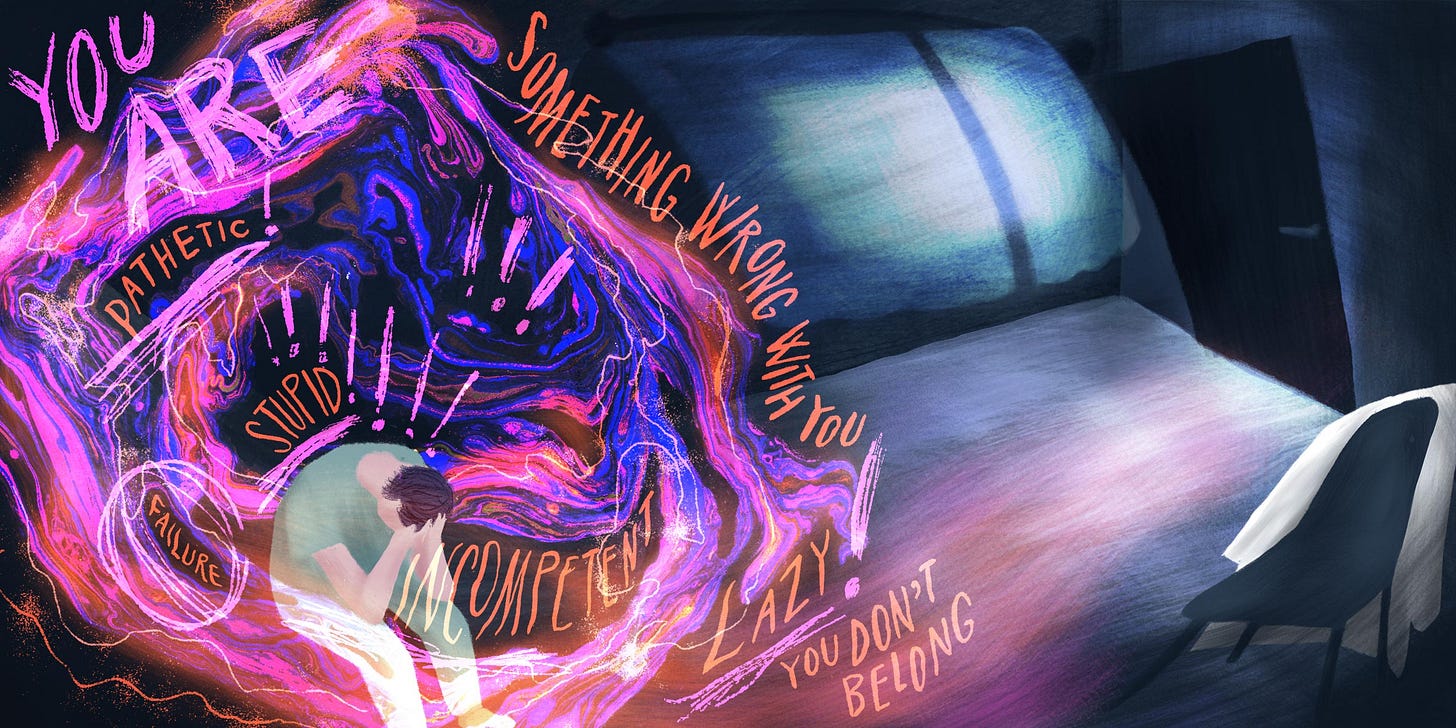

They start to spiral, the feelings are out of control and everything is becoming de-stabilised and distorted

After I had a shame experience recently, I felt my own version of this spiral: I was haunted by my own paranoia about my incompetence; my body felt too visible, my skin was suddenly hyper-sensitive and was fizzing with restlessness and the impulse to find somewhere safe to hide, to lock myself away. There was an overwhelming feeling of a lack of containment, and chaos: I didn’t trust myself, in the grip of feeling like I was “bad” or “cursed”.

I don’t think that we necessarily need a reference point from our own experience, in order to depict really strong feelings, but I do think it’s important to really listen to how people describe what it feels like to go through something - so that we can hear something beyond what we might expect them to say, and get to the physical sensation and the specificity of what overwhelm feels like.

If you want to learn more about shame, listen to the Shame and Medicine podcast ‘The Nocturnists’, created by some of the researchers I’ve been working with, who are really able to dig into the details of these feelings.

Thank you for reading! I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.