This month I’ve been taking people on a dance through pages of old books.

I’m teaching a small group of trainee doctors as part of a special compulsory creative module that medical students have to take part in during their training at the University of Exeter. The aim of the game is to introduce the students to creative ways of thinking so that they can draw on creativity to connect them more deeply with their humanity as doctors. This is my first year teaching on the training, and when I was planning how to introduce creativity into the lives of these highly skilled, knowledgeable strangers, I first of all decided to abandon the idea of image-making altogether, and start with storytelling.

You might think that storytelling and medicine don’t necessarily have much to do with each other, but I’ve been thinking a lot over the last few years about the relationship between narratives and illness. I started (and as yet have never finished) reading Darian Leader’s book Why Do People Get Ill?, which is a fascinating journey into the idiosyncrasies of symptoms, drawing attention to the idea that the time when we get sick, and how that sickness comes out, might be secretly saturated with cryptic messages or connections to significant relationships. I’ve been exploring for myself for a long time the ways in which my own recurring symptoms or chronic bouts of illness are related to relationships with family members, or hidden fears or furies that have no other way of being articulated. I’ve found some echoes of my own frustrations with illness in Alice Hattrick’s Ill Feelings, which explores the pain of entanglement with a loved one, when you bear close witness to their own disturbing cast of symptoms that parade around the stage floor of their life.

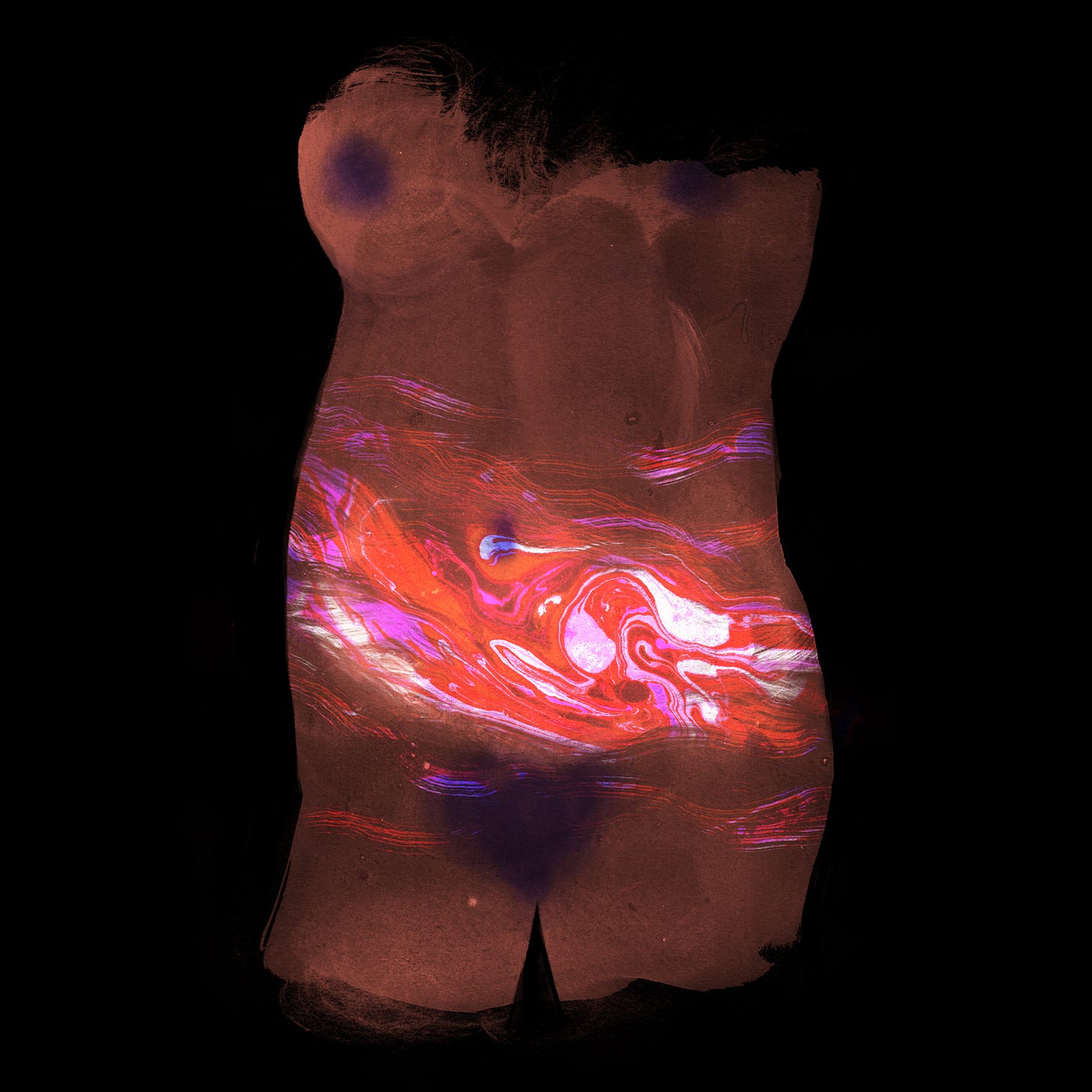

Above: Symptom, an illustration I made in 2020 when I was first starting to get interested in these ideas

When you’re a doctor, it might be the case that patients will report their symptoms to you in the form of some kind of narrative:

“It started last Tuesday when I noticed a pain in my side … / I’m really anxious that I might have cancer because my mum had it … / I can’t move my leg the way I used to…”

- these are approximations, but you can see how there’s a sense of time being marked in relation to a symptom, and that we might use coordinates like family members as important reference points for understanding the mystery of what is happening inside our own bodies.

With the medical students, I wanted to introduce them to the idea that it is possible to read beyond the surface of a narrative to find surprising, hidden meanings. One way to explore this is through creating ‘Blackout Poetry’.

It turns out it’s possible to get hold of loose, random pages of old books on eBay, so I ordered a bunch and took them with me to my session with the medical students. I gave them a page each and explained to them how we would go about creating poems from the words in front of us: to read through the page, and underline with pencil any phrases that on their own stood out as being interesting (working quickly without over-analysing it) and then using a marker pen, blacking out the rest of the text to leave those phrases behind.

Here’s the image above, typed out as a poem:

in search of adventure,

the enchanted,

lovers of the world,

go singing down the street.

loved, honoured and trusted most.

did worship no other

So things went on for many years,

The love

breaking

You will learn

envy

they poisoned the mind

We went around the room and read aloud our poems, sometimes giggling at the results, enjoying the spectacle of performing, without the vulnerability of having written any of the words ourselves.

You could say that this way of approaching a text turns it into nonsense, but it also allows us to see that words are beautiful, mysterious things that can collide with each other to produce unexpected narratives. When we approach a fixed story from a new angle, we can hear a different emphasis, which can enliven us to paying a different kind of attention. Perhaps there’s something in here that is useful for doctors: reminding ourselves that we don’t know how the story is going to go, and that even if a patient has come to us with something that we think we’ve heard many times before, if we listen to them in an enquiring way, we might hear frequencies that we would otherwise have never heard, and we might understand more about what they are trying to tell us.